Introduction

This article provides a walk through of patent data fields for those who are completely new to patent analytics or want to understand the workings of patent data a little bit better. A video version of the walk through is available here and the slide deck is available for download in .pdf, powerpoint and apple keynote from GitHub. This article goes into greater depth on each data field and their use in patent analysis.

This article is now a chapter in the WIPO Manual on Open Source Patent Analytics. You can read the chapter in electronic book format here and find all the materials including presentations at the WIPO Analytics Github homepage.

What is a Patent?

A patent can be described in two main ways:

- As a form of intellectual property right.

- As a type of document.

Understanding the structure of patent documents and data fields is the essential foundation of patent analytics. However, for those who are new to the patent system it is worth highlighting the key features of patents as a form of intellectual property right.

As a form of intellectual property right

- A patent is a temporary grant of an exclusive right to a patentee to prevent others from making, using, offering for sale, or importing, a patented invention without their consent, in a country where a patent is in force.

- Patent rights are territorial rights - they are only valid in the territory of the country where granted.

- Patents are typically granted for a period of 20 years from the filing data of an application but may be opposed or revoked.

- To be eligible a claimed invention must:

- Involve patentable subject matter

- Be new or novel

- Involve an inventive step

- Be susceptible to industrial application or useful.

Patents as a type of document

For patent analytics we need to concentrate on patents as a form of document and to understand:

- The structure of patent documents and their data fields.

- The strengths and limitations of different patent databases as a means for obtaining patent data.

In this chapter we deal with the basics of patent documents and their data fields.

Basic Data Types

When performing patent analysis we are dealing with data of seven different types:

- Dates (priority, application and publication dates)

- Numbers (priority number, application number, publication number, family members, citations)

- Names (Applicants - also known as Assignees - and Inventors)

- Classification codes (e.g. International Patent Classification/Cooperative Patent Classification)

- Text fields (Title, Abstract, Description, Claims, Sequence data)

- Images (Diagrams)

- Additional Information (Legal Status, Public Registry etc.)

We will walk through each of these fields using a patent application for synthetic genomes from the J. Craig Venter Institute as an example. In the electronic version each of the titles for the images are hyperlinked to their sources to make it easy to explore the data as you go through them.

Synthetic Genomes

Synthetic biology (and synthetic genomics) began to hit the international headlines with the news in 2010 that members of the J. Craig Venter Institute had successfully synthesised the genome of a Mycoides microbe and transplanted the genome into the empty cell of another Mycoides that then booted up. This led to considerable excitement about the creation of artificial life and is part of the story of the growing prominence of synthetic biology. For our purposes it is an interesting example for walking through standard patent data fields.

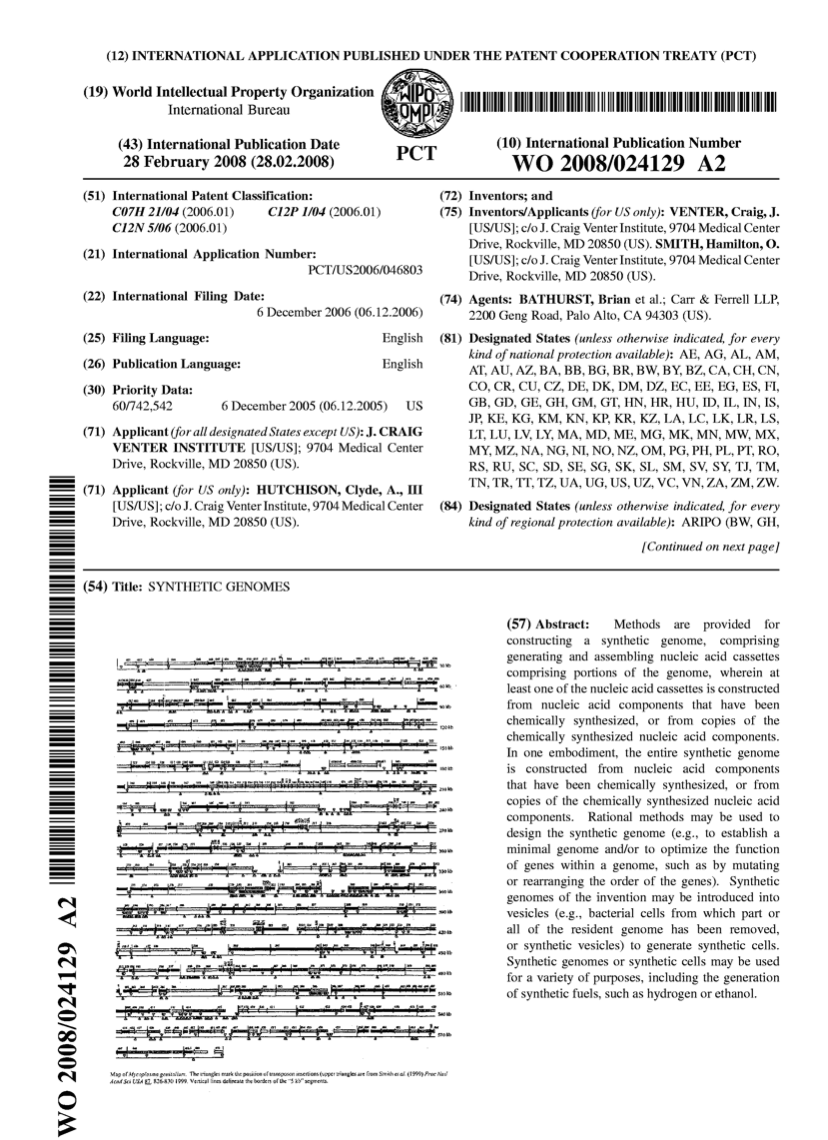

Original Front Page

What we see below is the front page of an international Patent Cooperation Treaty(PCT) application from the J. Craig Venter Institute on Synthetic Genomes. The PCT allows applicants to submit a single application for potential consideration in up to 148 other countries that are Parties to the PCT based on decisions made by applicants and examination decisions in individual countries and regions. The front page (or biblio) displays the data fields that are typically used in patent analysis.

Starting with dates. There are three dates on this application.

- The first date is the

priority date(6 December 2005) in thePriority Datafield (30). This refers to the original (first filing date) for a US application that is the priority (or parent) of all later filings of the same application anywhere else in the world (known as a patent family). - The second date is the

International Filing Date(22) which is 12 months after the priority filing (US60742542). - The third date is the

International Publication Date(field 43) which is just over 24 months after the international filing date and 3 years from the first filing date (priority application).

For patent analytics the most important dates are generally the priority date (06.12.2005) and the publication date (28.02.2008). The priority date is important for two reasons. First, in legal terms, it establishes the priority claim for this claimed invention over other claims to the same invention submitted in the same period or later under the terms of the Paris Convention. Second, in economic analysis the priority date is the date that is closest to the investment in research and development and therefore the most important in economic analysis (see the OECD Patent Statistics Manual ). However, this information only becomes available when an application is published. That is typically 24 months from the original filing date. As a result this information falls off a cliff the closer we move towards the present day.

The publication date is important because, like the publication number, it is generally the most accessible in patent databases. However, in this case there is a 2 to 3 year lag between the first filing date and the publication date. For patent analysis this means that counts based on publication date are always displaying trends that are 2 to 3 years after the original activity has taken place. However, because applicants must pay at each stage of the process patent publication data can be useful as an indicator of demand for patent rights in one or more countries. In many cases the publication date will be the only date that is available to map trends.

One important lesson from understanding patent date fields is that patent data is always historic. That is, it always refers to activity in the past.

We will address other data fields below. For now note the applicant and inventor information including address and other useful information for patent analysis on the front page (fields 71 and 72). Also, note the International Patent Classification data as an indicator of technology areas expressed through alphanumeric codes (e.g. C07H21/04 which tells us that the claimed invention involves nucleic acids). We also see text fields (for text mining) in the title and abstract and finally we have an image with information on DNA cassettes forming part of the invention.

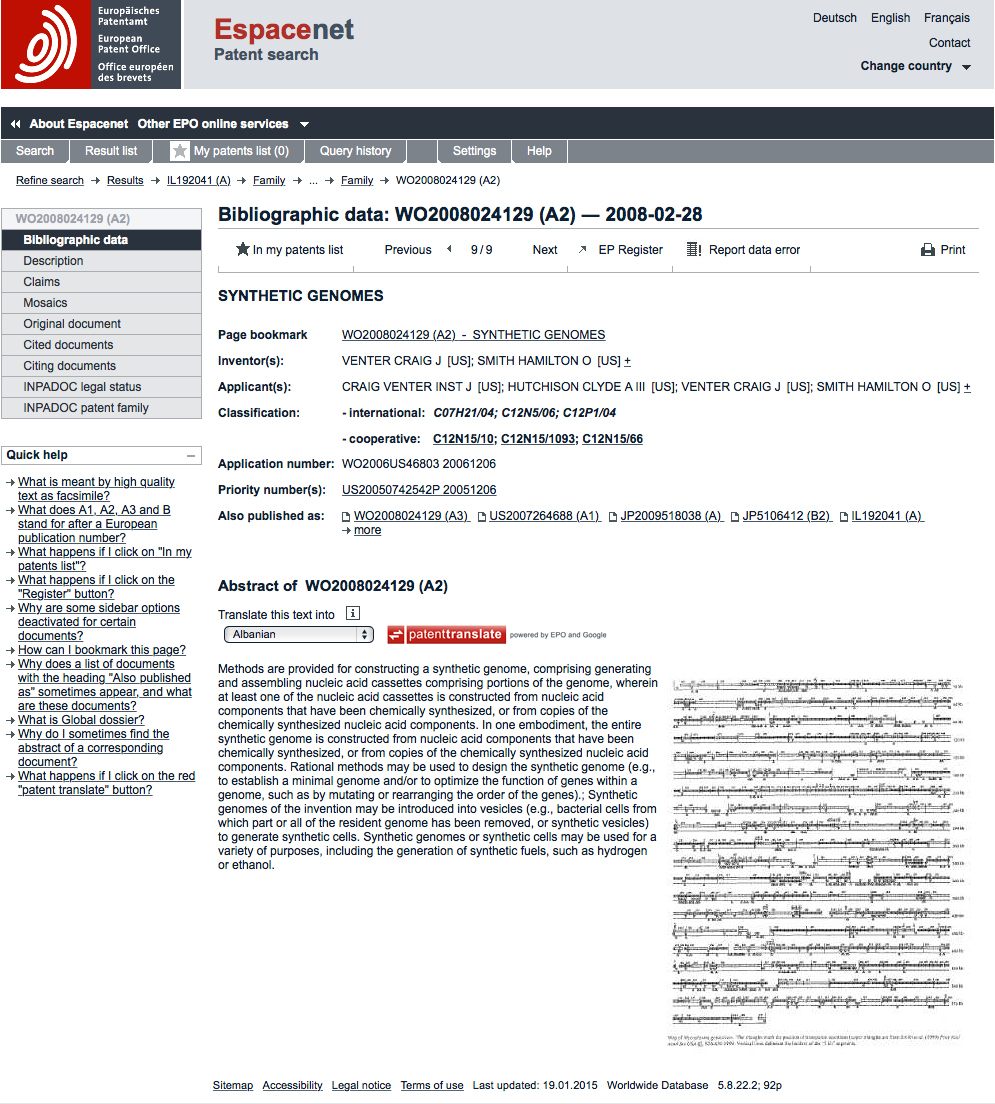

espacenet Front Page

Here we can see the same information in the front page for the record in the espacenet database. espacenet is easily accessible and popular. Even when using commercial tools espacenet is often the fastest way to look up or check information. For a brief overview see these videos and the interactive espacenet assistant.

In this case we see data in the form that will typically come back from a patent database such as espacenet. Starting with the dates, we can see that the priority number field contains the priority (first filing) date 20051206 (as YYYYMMDD), linked to the priority document US20050742542P, a provisional US application. This is followed by the application number WO2006US46803 and date and the publication number and date. The publication number, WO2008024129A2, is normally the easiest to use when searching a patent database.

Other things to note are that the Applicant and Inventor fields include country code information (e.g US) using standard two letter country codes. While this information is not always available (notably for filings purely on the national level) this data is very useful in patent analytics for identifying cross country collaborations between inventors and applicants. However, be aware that for statistical use it is important to calculate the number of records that possess this country information or to use only those jurisdictions where this data is recorded.

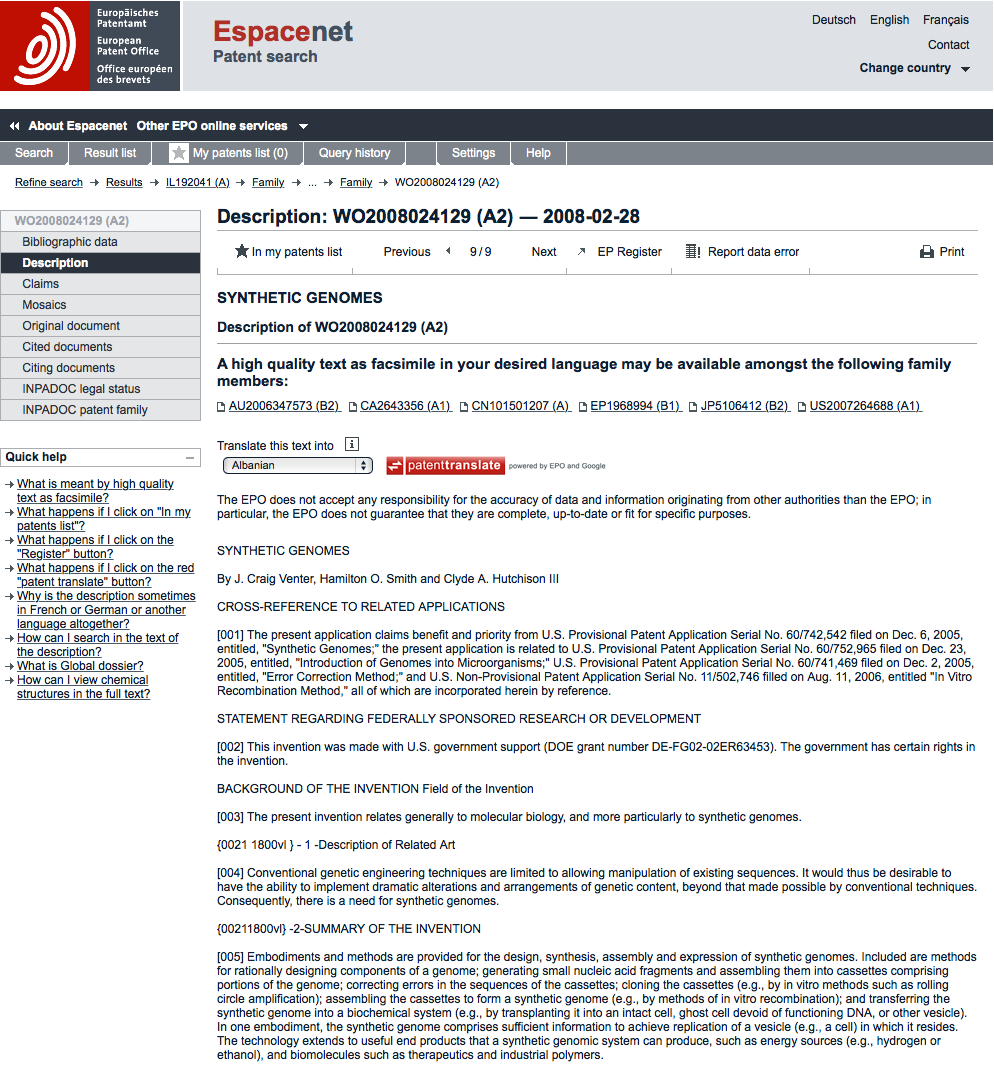

Description

The description section (also called the specification) contains details on:

- previous patent filings and prior art such as scientific literature.

- in the case of the United States, applicants include information on whether the research leading to the invention was government funded including the funding agency and relevant contract number.

- a summary followed by detailed background to the claimed invention. This will typically include examples which may be actual worked examples or paper (prophetic) examples.

Data provided in the description can be very useful where text mining approaches are applied. For example, the authors have previously text mined millions of documents for biological species names as in this article. In other cases, it may be desirable to investigate the description for information on the country of origin of materials and traditional knowledge, or to explore the uses of particular extracts or chemical compounds.

However, when working with data in the description note that it is often noisy and care is required in constructing a query. For example, a search for pigs will capture lots of data on pigs as animals but also toy pigs and devices for cleaning pipelines (pipeline pigs). In contrast, searches for a country name (such as Senegal or Niger) may produce thousands of results that have nothing to do with that country because they are part of species names (e.g. Acacia senegal or Aspergillus niger).

It is therefore important to carefully consider and test search queries for text fields such as the Title, Abstract, Description and Claims to avoid being overwhelmed by irrelevant results.

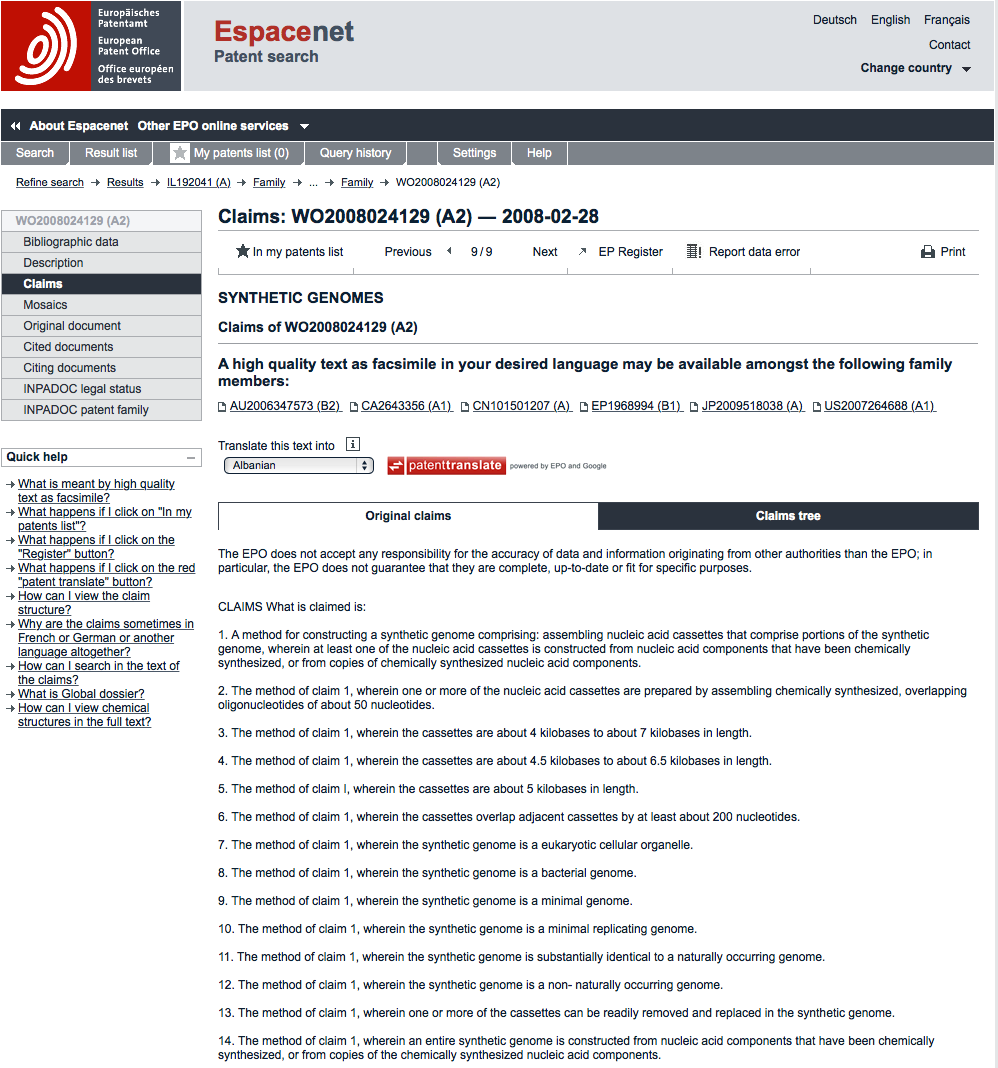

Claims

The claims section of a patent document is commonly regarded as the most important part of the document because it tells us what the applicant is actually claiming as an invention. What is claimed in a patent application must be supported by the description. For example, one could not insert a section of Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice” into the description for a synthetic genomes applications and expect it to go forward. Furthermore, in countries such as the United States, patent claims are interpreted (constructed) in light of the contents of the description (see this informative 2009 article by Dan Burk and Mark Lemley on debates in the US).

Patent claims take a variety of forms and what may be permitted may vary according to the country or jurisdiction or take specialised forms (e.g. Design patents or US Plant Patents). That can make describing and interpreting patent claims difficult. For more detailed discussion see the WIPO Patent Drafting Manual with examples from the manual below, see pages 84-90:

- Compositions of matter (e.g. an extract, a compound).

- Apparatus (e.g. a stand for a camera).

- Methods (e.g. methods for amplifying a nucleic acid or for making tea).

- Process (e.g. processes for producing a particular product such as tea, known as Product by Process Claims).

- Result to be Achieved/Parameters. (e.g. an ashtray that automatically extinguishes a cigarette).

- Design claims (e.g. a specific design for an umbrella).

- Plant patents (limited to certain jurisdictions, generally 1 claim for a distinct variety of a particular cultivar e.g. of Banisteriopsis caapi named ‘Da Vine’). Restricted to the claimed cultivar and not to be confused with a utility patent as in the Ayahuasca controversy).

- Biotechnology claims tend to take the form of “An isolated polynucleotide selected from…” followed by sequence identifiers (SEQ ID).

- Use Claims. In some jurisdictions, an applicant may claim a new use for a known compound. For example, the use of a well known compound for the treatment of a disease (where that has not previously been described).

- Software Claims. Jurisdictions also vary on whether they permit software claims (and the law is also subject to revision). Examples include references to “A computer-readable medium storing instructions…” or “A memory for storing data for access by an application program…” followed by further details on the data structure and objects.

- Omnibus claims: such as “1. An apparatus for harvesting corn as described in the description. 2. A juice machine as shown in Figure 4.”

While this sounds like a lot of different types of claim in practice you do not encounter all of these all the time. In our experience (mainly working on biological issues), the claims tend to be for compositions of matter, including biotechnology above, and methods. That could vary depending on your field of interest.

In the case of the synthetic genomes patent application we can see that we are dealing with a method claim (claim 1) relating to the assembly of nucleic acid cassettes. The first claim is the most important (and often the most useful) of the claims because everything else that follows normally depends on that claim.

Claims can be divided into independent and dependent claims and they form a claims tree. In this case claims 2 - 14 depend on claim 1 and this can be identified by the reference to “The method of claim 1” at the beginning of each of these claims. The next independent claim in WO2008024129A2 appears in claim 32 for “32. A synthetic genome”. Independent claims do not depend on the other claims.

One final note on patent claims for patent analysis is that claims may be cancelled or may be modified in particular jurisdictions. In some cases an examiner may determine that there is more than one invention in the application. This can lead to the application being divided into separate applications linked to the original application (although rules vary on this). As such, depending on the type of analysis required it can be important to trace through applications into different jurisdictions. This is where the patent family comes in.

Family Members

In the discussion above we noted that when a patent is filed for the first time anywhere in the world it becomes the priority filing or, as the authors tend to call it, first filing. The priority filing also becomes the parent for any follow on publications in that country or another country (applications and grants, including administrative publications such as search reports or corrected documents). The priority filing is therefore the founder of a patent family and the later documents are children who are family members. Because this can lead to quite a lot of confusion let’s look at this example.

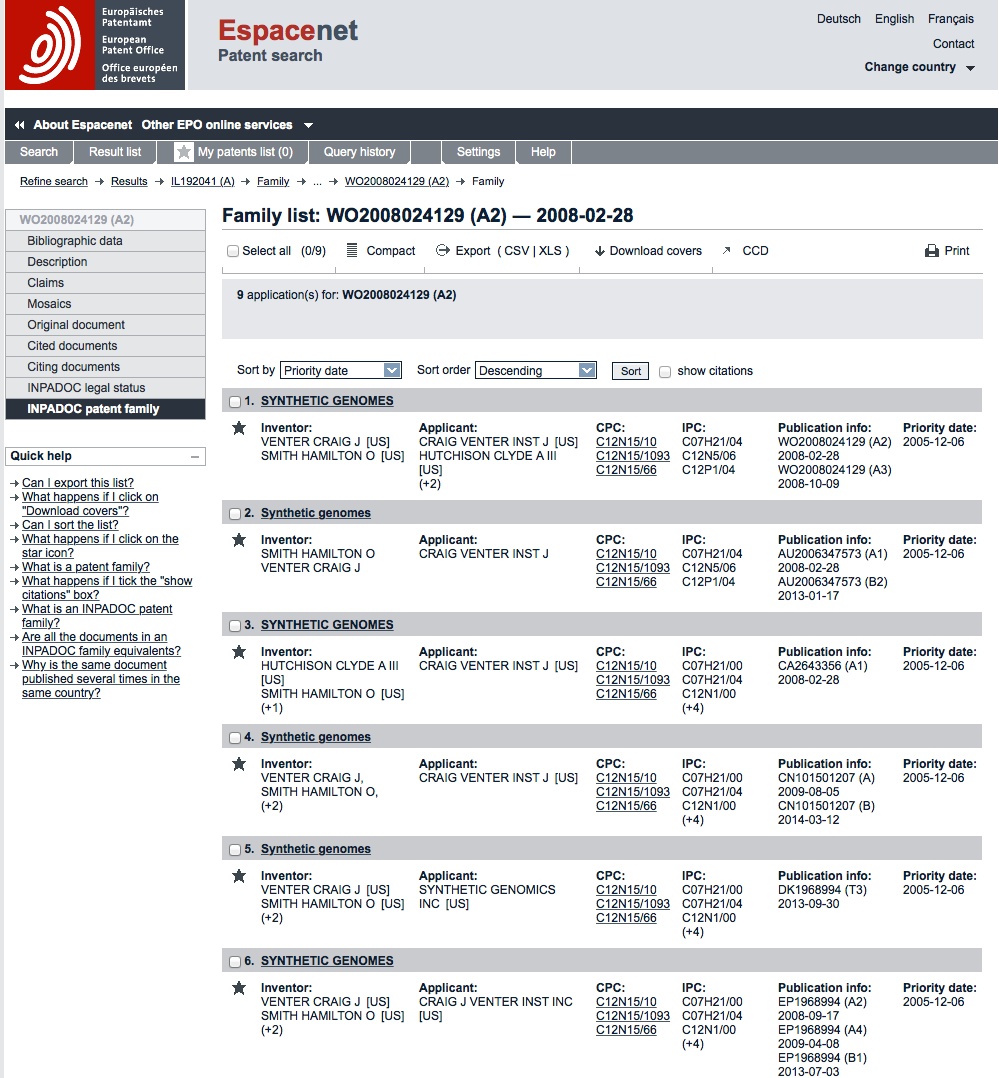

We can see here that the family of our international application on synthetic genomes contains 9 applications (including the WO reference document). We can see that in some cases these 9 applications have led to more than one publication leading to a total of 15 family members. Patent publication numbers are generally accompanied by two letter codes at the end of the numbers called kind codes (e.g. A2, B1, T1 etc.) These codes in technical terms tell us about the publication level but also about the type of document involved.

In some cases these are administrative republications. For example, for the Patent Cooperation Treaty (WO) kind code A3 means publication of the international search report. While this is a family member we would not want to include counts of these documents in patent statistics unless we were studying actions by patent offices.

In contrast, AU is the country code for Australia and it has two documents with kind codes A1 and B2. Because patent offices vary in their use of these codes they can be difficult to accurately interpret, for more details see this list. In the case of Australia kind code A tells us that this was the publication of an application and kind code B tells us it was also published as a patent grant. When we scan down the list of family members we can see that there are a number of other countries with publications of type A and B.

The interpretation of kind codes requires considerable care because patent office practices also vary over time. For example, prior to 2001 the United States Patent and Trademark Office only published patent documents when they were granted and did not publish patent applications. Also, until 2001 the USPTO either did not use kind codes or used kind code A. From 2001 onwards the USPTO published both applications and grants with applications receiving kind code A and grants receiving kind code B. Knowing this is critical to the calculation of patent trends because the pre-2001 data needs to be adjusted.

Having said this, as a general rule of thumb, and with the exception of the United States prior to 2001, kind code A can be taken to mean an application and kind code B as a patent grant. While we would emphasise that this is not entirely satisfactory it is the best proxy available for counting data across countries until patent offices adopt more uniform practices. However, where dealing with a single country it is better to explore the significance of each type of code.

Patent family data thus provides us with a route to identifying all other documents that are linked to an original first filing. Through an understanding of patent families we can also make progress in distinguishing between patent applications and patent grants (although this is imperfect) for the purpose of developing statistics. While this is satisfactory for developing analysis of patent trends, for other purposes we would want to explore other information (such as whether a patent grant is being maintained… see below).

When working with patent data there are a variety of patent family types. For example, the EPO Documentation Database (DOCDB) is the central source of most patent data and has a DOCDB family system. In addition, the International Patent Documentation Centre (INPADOC), now part of the EPO, established the widely used INPADOC system. espacenet database families are a little bit different to INPADOC families. In addition Thomson Reuters uses the Thomson system. For an important in depth discussion of patent families in relation to patent statistics see the excellent OECD STI Working Paper by Catalina Martinez (2010) Insight Into Different Types of Patent Families. This basically demonstrates that DOCDB families are a little smaller than INPADOC families. Thomson families tend to be ignored in patent statistics because they are limited to commercial users of the Thomson platforms. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t use them, but that if developing work on patent trends that others can follow then DOCDB or INPADOC families makes much more sense. In the author’s work we tend to always use INPADOC family data where it is available.

By now, this may sound rather complicated. In practice, it isn’t. A very simple way of understanding a patent family is as follows. A patent family is a stack of documents with the parent (priority) at the bottom of the stack. Those documents may have been published in multiple countries and in different languages but because they link back to the same parent (priority) they are members of its family.

This simple approach to understanding a patent family is also very useful when thinking about what to count.

- When we develop counts based on a patent families we are counting the first filings of a patent application and nothing else. That is, the document at the bottom of each stack.

- When we count patent family members we are counting all documents that link to the patent family as its parent. That is, all documents in the stack.

The above approach will allow you to successfully count thousands or millions of patent documents in a way that makes sense to you and to others. However, bear in mind that in some cases a patent may have more than one priority parent. This appears to be particularly true for software patents. That is we are confronted by a “many to many” relationship rather than a simpler “one to many” relationship between the priority documents and family members. Additional measures would therefore be needed to develop counts to address this aspect of the data.

Cited

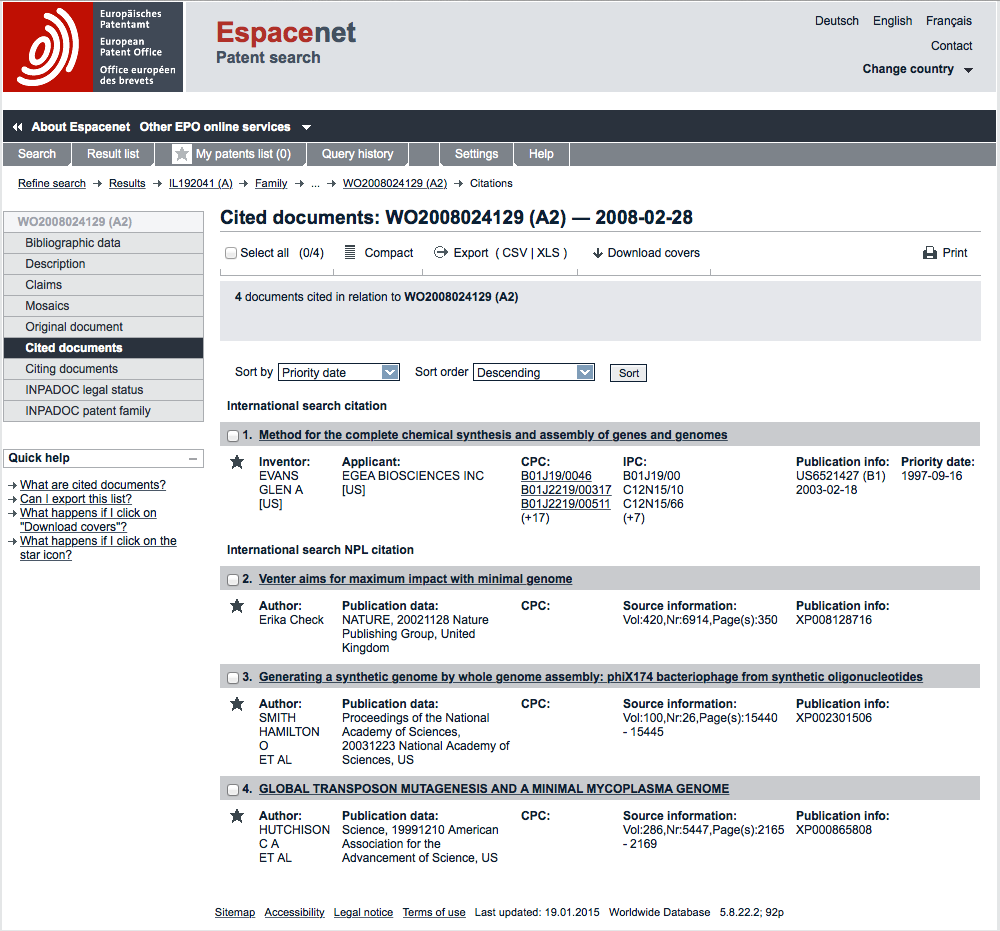

Patent applicants can be said to be “standing on the shoulders of giants” to borrow from the work of the economist Suzanne Scotchmer on patents. For our purposes, judgements about novelty and inventive step during examination are based on assessments of the existing patent literature (what others have previously claimed) and what is called the Non-Patent Literature (NPL), including scientific publications and other materials constituting “prior art”. The existence of prior art may mean that a patent application cannot proceed or that applicants will need to limit what they claim to the aspects of the invention that do not exist in the prior art. This information is recorded in the Cited documents field in databases such as espacenet.

In this case the cited documents include a 2003 US grant US6521427B1 to Egea Biosciences with a priority filing in 1997 related to oligonucleotide synthesis for “the assembly of genes and genomes of completely synthetic artificial organisms” using computer directed gene synthesis. In addition, cited documents include cited literature (awarded an XP code in espacenet) that in two cases originate from the inventors of the synthetic genomes application.

Cited patent and non-patent literature may have two sources.

- Information provided by the applicants

- Documents identified by examiners during search and/or examination. In some countries, applicants are required to provide detailed information on prior art relevant to the claimed invention. In other cases the requirement is weaker. As we might expect, applicants will be reluctant to disclose information that invalidates or greatly complicates their efforts to secure a patent. In addition, examiners will also perform searches to identify relevant art but requirements on examiners to actually disclose that information may also vary. For discussion see work by Colin Webb and colleagues at the OECD here and the 2009 OECD Patent Statistics Manual, notably Chapter 6. Citations added by examiners are generally speaking more important than those added by applicants and in some cases may be marked in patent databases. In this particular case we could find additional information on the origin of the citations by looking at the original document for the publication of the international search report (A3 document) mentioned above in WO2008024129A3. As we can see this contains the front page and then a set of citations accompanied by a category where the entry marked X for the patent grant to Egea Biosciences is judged to affect the claims to novelty and/or inventive step when taken on its own.

In practice, applicants may use citations to adjust their claims and as such citations are not necessarily an obstacle to obtaining a patent grant (as we have seen in the patent family data). However, depending on our purpose, citation data is very useful in patent analysis.

- It makes it possible to gather relevant patent data that might have been missed because of the limitations of a particular search query. It thus helps to complete the picture for a patent landscape analysis or searches of relevant prior art.

- For academic research it can display the activity that influenced the emergence of a particular field such as synthetic biology.

When reviewing cited patent and non-patent literature note that a cited patent document (which may be an application or a grant) may not fall directly into the field of invention of interest. For example, a particular feature of a claimed invention in one technology field (such as military optics) may affect developments in another field (such as medical optics) or be apparently completely unrelated except for a specific technical aspect.

Citing

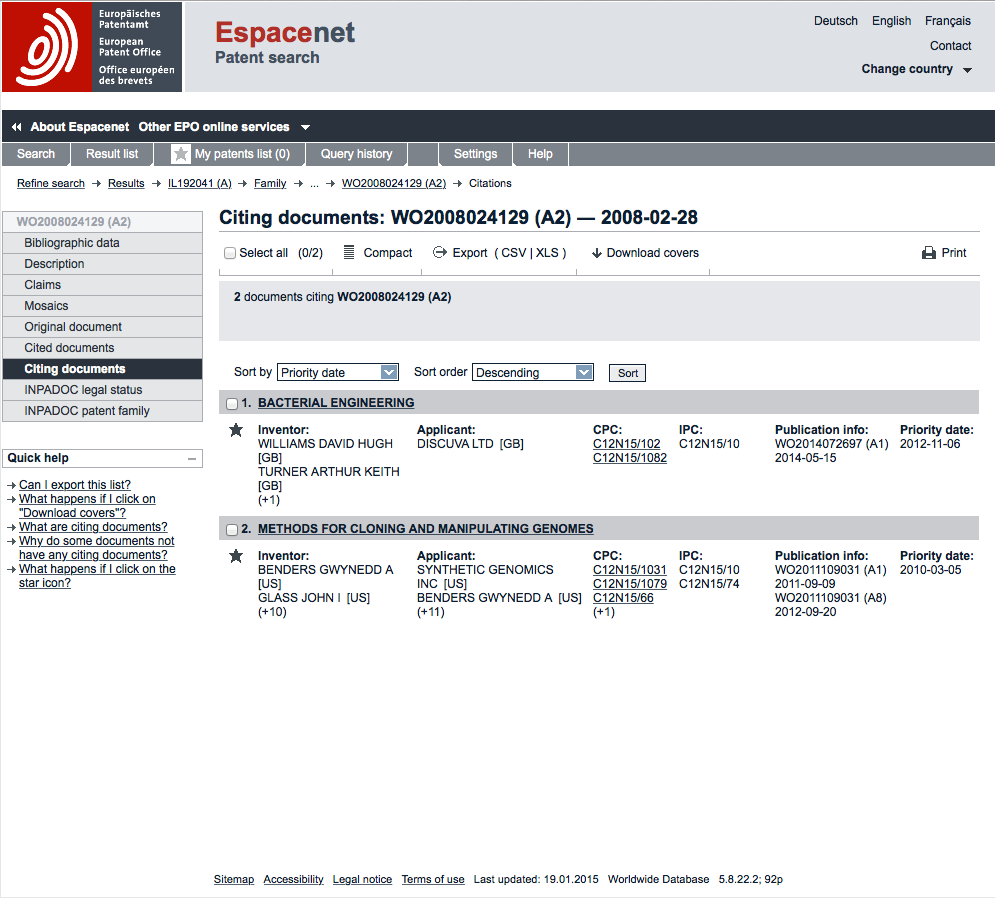

Citing data is the opposite of cited data. One useful way to think of this is that cited data means back citations while citing data means forward citations. Citing data or forward citations are later patent applications that cite our reference document as follows.

In this case there are two citing documents at the time of writing. One is from UK applicant Discuva for bacterial engineering WO2014072697A1. A second is from Synthetic Genomics (a commercial arm of the J. Craig Venter Institute) for methods for cloning and manipulating genomes with some of the same inventors listed on the application WO2011109031A1.

Forward citations provide information on the applicants who are being affected by a particular patent application or grant or, on a larger scale, by sets of documents. This data can be used in a strategic way to identify others working in a particular field that is ‘close’ to a company or university’s area of interest. This information could inform decisions on building potential alliances or, in other circumstances, it may inform decisions on infringement proceedings.

In broader terms, forward citing data can inform patent landscape analysis on the development of a particular field (such as synthetic biology), while bearing in mind that patent activity in one field may have spill over effects in other apparently unrelated areas of technology.

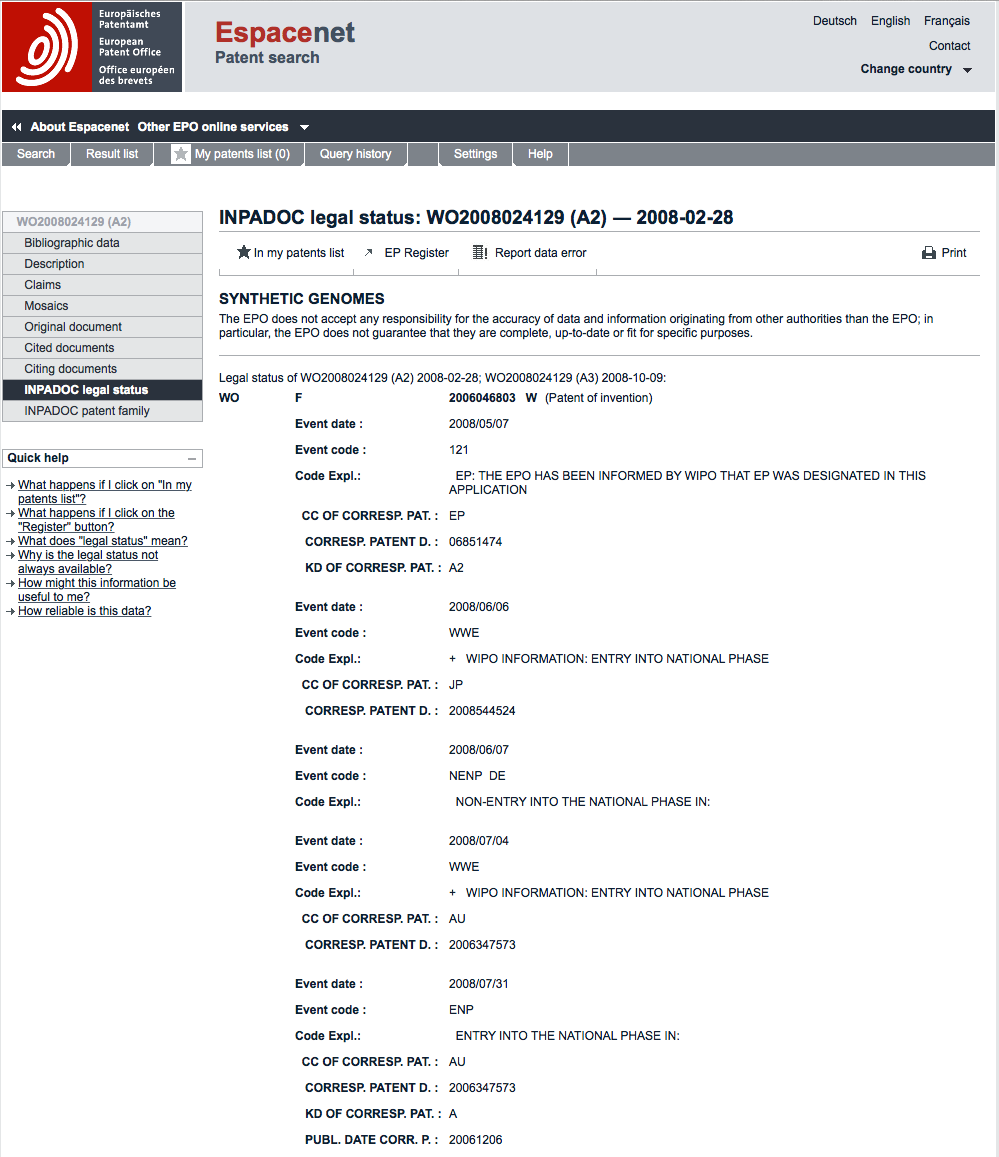

Legal Status

As discussed above, patent kind codes at the end of publication numbers provide an indication of the publication level and type of patent document. In cases where this involves specific kind codes (e.g. B) this is often an indicator of a patent grant. However, to gain additional insights we need to review the legal status data as below.

In this case the most obvious point about the data is that it informs us that the application is entering the national phase in a number of different countries. That is the applicants are pursuing the application in specific countries listed in the front page (above) under the Designated States field (all Contracting States to the PCT are listed by default). As such, the applicants are signalling their intention to pursue patent grants in these countries. In other case, the legal status data may indicate that an application has been rejected, that a granted patent has lapsed due to failure to pay fees or has expired. Additional information may be obtained through the interpretation of legal status codes with more information available by downloading the Categorisation of recently used legal status codes from the EPO website.

When reviewing legal status data note that it may not be recent or complete. For this reason investigation at the national level (and consultation with a patent professional) will generally be necessary to determine what is happening with a particular application or grant.

Patent Registers

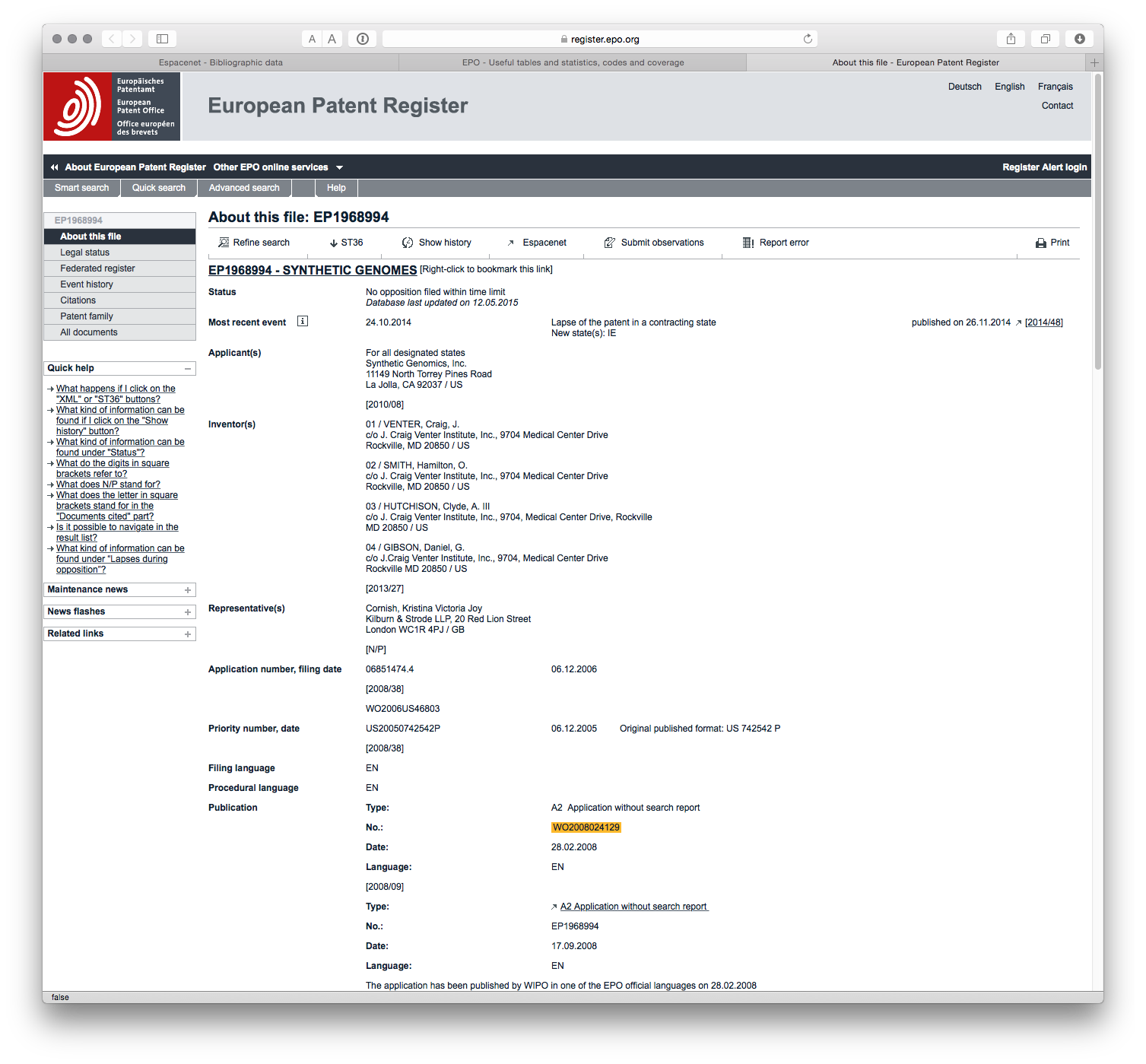

Additional information on a patent document is typically available by consulting patent registers on the national or regional level. In the case of European level applications, more information is typically available through the EP Register button on the front page. If we select this for our WO document we will be taken to the EP Register entry for the European family member EP1968994. As below.

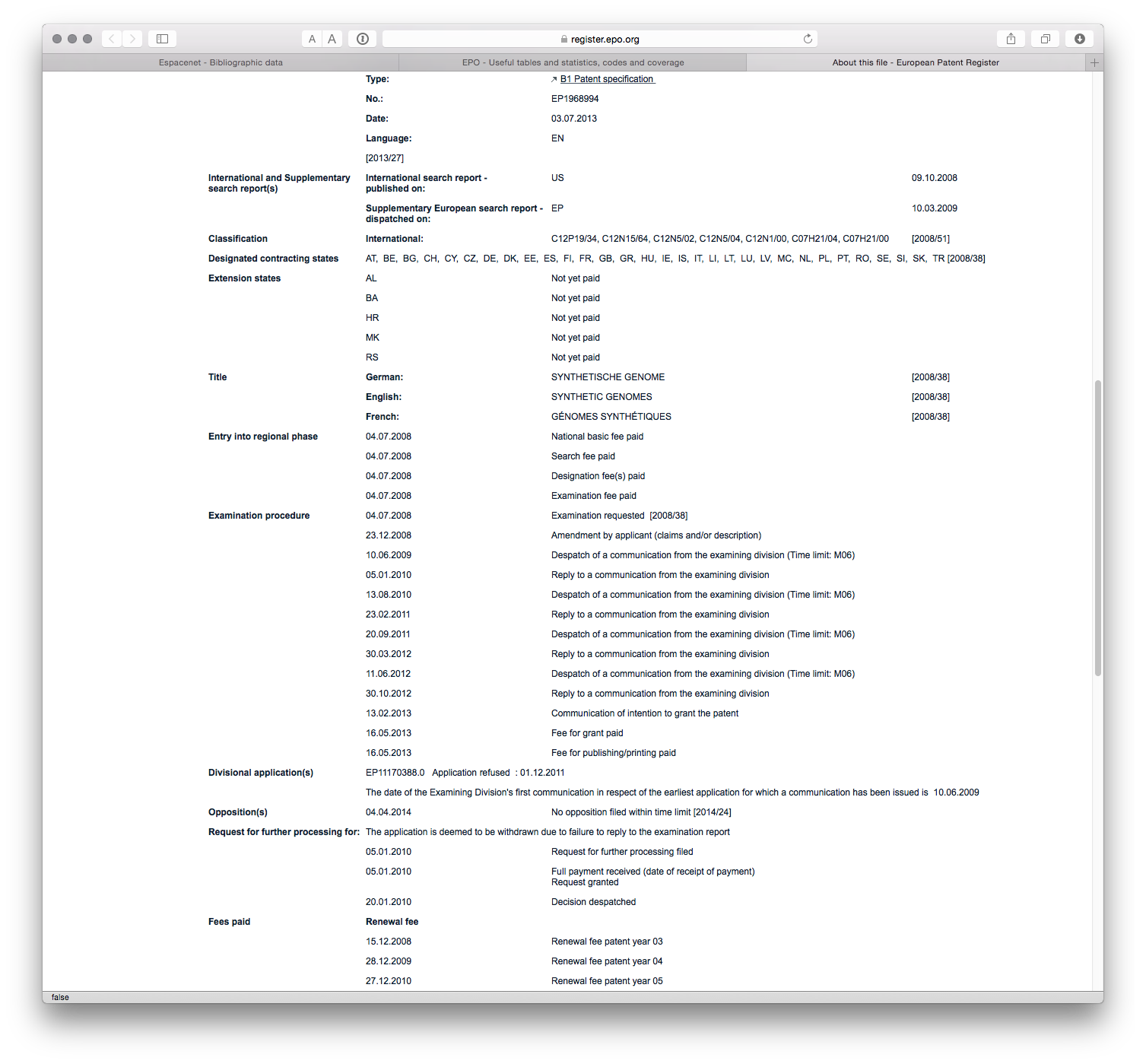

From this information we can see that no opposition to the patent application was filed within the time limit. We then see that the most recent event is a lapse of a patent in Ireland (IE) along with the publication history. If we scroll down the page more information becomes available.

From this information we can see that no opposition to the patent application was filed within the time limit. We then see that the most recent event is a lapse of a patent in Ireland (IE) along with the publication history. If we scroll down the page more information becomes available.

In this case we gain access to information on the written communication history between applicants and the EPO along with details of the payment of patent renewal fees. Out of sight on this image is citation data including the DOIs of cited literature that will link directly to the article concerned where available.

On the menu to the left additional information is available. The federated register menu provides access to the national patent registers of designated contracting states under the European Patent Convention as can be seen here.

Finally, the menu item All Documents provides access to copies of available correspondence and other documents that can be downloaded as a Zip archive. It is also possible to submit a third party observation using the submit observations button in the menu.

Data within the register can be particularly useful for exploring the history and status of an application such as the modification of patent claims in light of search reports. It is also very useful for identifying and reviewing opposition to a particular application.

Within Europe it is quite easy to consult register detail. To assist with accessing registry information in other countries WIPO has recently launched a Patent Register Portal to simplify the task of locating the patent register in countries of interest.

Round Up

In this chapter we have walked through some of the most important patent data fields using a single example and the espacenet database. As can now be appreciated a basic understanding of patent data fields opens ups a lot of additional information about a single document of interest.

These basic fields are also the building blocks for sophisticated patent analysis. In future articles we will focus on:

- Retrieving data with these fields

- Cleaning up the data in these fields

- Mapping Trends

- Network Mapping

- Geographic Mapping